Research on Employment Relations and Social Inequality

Jun Imai, Professor

Faculty of Human Sciences, Department of Sociology

- Research

【Abstract】

The aim of this research is to use the concept of “industrial citizenship” to explain structural

inequality in Japanese society and the mechanisms that reproduce this inequality. It is impossible to explain structural inequality in Japan just using the common Western concept of “class,” as employment patterns, the size of companies, and gender are important variables in regard to status.

This research asserts that a form of industrial citizenship that is unique to Japanese society is behind the formation and reproduction of this distinct type of inequality. The original concept presented by T. H. Marshall (1950) shows employment relations unique to modern society formed through interaction between workers, employers, and the state and it ultimately focuses on the building of social relationships comprising norms of rights and obligations established between workers and employers within specific employment patterns, or in other words, their social positions.

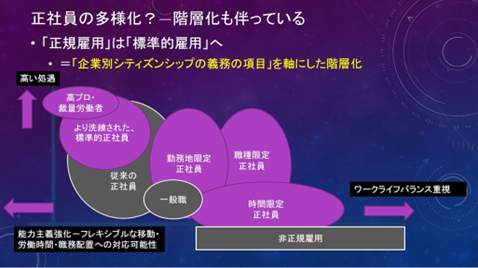

In Japanese society, a more suitable name would be“ company citizenship” as the positioning of regular salaried employment by individual companies is established based on the rights of seniority wage and corporate welfare and the obligation to fulfill the various demands of the company in terms of flexibility (flexibility in regard to overtime, job rotation, and relocation).

This research asserts that despite the reforms to the labor market over the last few decades, the recognized frameworks and behaviors of workers, employers, and the state have been trapped by this citizenship as the norm. Accordingly, there has been an increase in non-regular categories of employment, the concept of equal pay for equal work now exists in name only, and the formation of limited regular employment systems with the aim of equality and diversity ironically created, a hierarchy within regular employees.

Put simply, industrial citizenship is the recognition and sense of equality and fairness that we expect within an industrial society centered on employment. In Japanese society, this sense has developed as the thought that to be a decent worker who contributes to the company, or in other words, to be a worker who deserves the rights of seniority wage, lifetime employment, and corporate welfare, means not only fulfilling demands in terms of job allocation and rotation, but also demands for overtime work and job relocation that involves regional transfer. A person who accepts these rights and obligations as norms is suitable for a regular employee position and a career as a regular employee means long-term competition with coworkers who share this same sense of position.

This sense of citizenship justifies seeing people who do not share these norms as being lower in status and therefore not deserving of the same rights. The current legislation that is believed to correct the disparity between regular and non-regular employment in our society was made without critically grasping this sense. Ironically, it has ended up justifying this inequality and exclusionism.

For example, if a non-regular employee receives lower pay for almost the same work as a regular employee, the explanation will be that “They do not have a responsibility to the organization,” (i.e. they do not share the constant possibility of overtime or relocation faced by a regular employee) and current legislation confirms this. It has just enshrined the existing disparity between what is considered regular and non-regular into law, based on extant concepts of equality and fairness, and justified it, showing that there has been virtually no progress made on correcting the disparity and exclusionism.

【Future prospects】

This research has led to the publication of a book: Employment Relations and Social Inequalities: Social Structural Changes Shaped by the Development of Industrial Citizenship (Yuhikaku Publishing).

In this book, I point out that going forward, the willingness to accept transfers in line with a company’s demands will become the standard used to sort employees into a hierarchy. Under this logic, many companies’ current efforts to diversify their regular employee will actually end up stratifying this workforce.

Going forward, research will focus on where movement to stop this trend will originate.